The indigenous African religious customs are typically popularized as a form of monotheistic animism. However, the very definition of animism, stemming from Edward Tylor’s Primitive culture in 1871, raises the question of whether animism can be perceived as a religion, or whether the definition applies to African practices, are still debated. A symbol of this difficulty in characterizing this cultural and religious tradition is that the current terminology of “African traditional religions” only appeared recently, in 1965.

The common features of traditional African religions encompass the belief in the existence of a supreme being, creator and organizer of the universe. He is generally described as distant from men and inaccessible. Alongside this, there are spirits, including those of the ancestors, as well as minor divinities connected to nature (such as water spirits). These spirits are frequently invoked because they are likely to intervene on Earth to favor those who invoke him or to restore troubled order (illness, bad harvests, etc.) and harmony in the world. Indeed, the difficulties of life and society are considered to be caused by the violation of taboos and social rules.

The rituals, including initiation rituals, are numerous and highly codified and are practiced under the aegis of religious experts (such as oracles, healers, etc.). Unlike the religions of the Book, there is no written dogmatic corpus in the African traditional religions (sacred texts), and the transmission of the related knowledge is oral. Associated with them are numerous and diverse representations in the form of statuettes, masks, etc., classics of African art.

Traditional religions are most often specific to an ethnic group and a given geographical area; however, itinerant ethnic groups can spread them over vast territories. Some religions have even spread, mainly via African slaves, such as voodoo in Haiti, Santeria in Cuba, and Candomblé in Brazil.

Traditional religion leads to a worldview where the sacred and the profane are strongly intertwined: “Traditional African religion was (and remains) inextricably linked to African culture”; there is no distinction between religion and culture since it is always possible to interpret what happens in the prosaic world as being caused by the action of divinities or spirits. Thus, it is customary to say that in Africa, one never dies a natural death: “The expression natural death does not cover the same semantic field in Africa or in the West. In Africa, death results from an intervention (fault of the deceased = violation of the taboo, revenge of the enemy, curse of the sorcerer).” Between religious practice and cultural practice, the status of certain rites is sometimes difficult to define. In 1972, Bwiti was defined by some authors as a “mixed initiatory society which is increasingly tending to become a true religion.”

This worldview has a political impact. The leader simultaneously carries the political, secular aspect, for example conflict management; at the same time, he is an intercessor with the sacred and most often shares his power with other intercessors. This remains true in the present era, especially in rural societies, although not only.

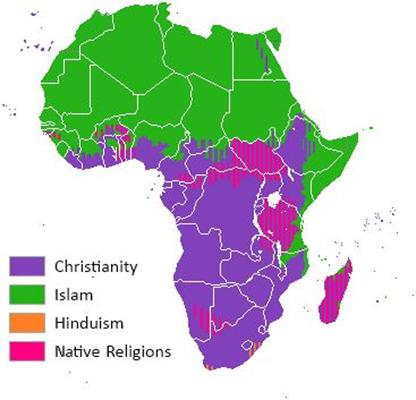

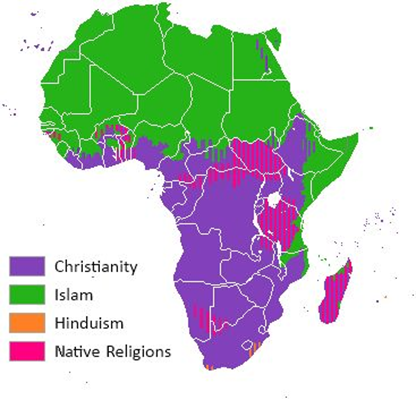

This interweaving explains the syncretisms that appeared in sub-Saharan Africa on the occasion of the establishment of imported religions, Islam and Christianity.

For more information :

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

- https://africacenter.org/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024