Massively used since its invention in the 19th century, the concept of ethnicity is nevertheless still widely debated today as to its definition and scope. An eternal fact of the continent for some, a largely colonial invention for others, in addition to being poorly defined, the ethnic concept is accused of sometimes being used wrongly, where social analysis without ethnic coloring would suffice.

Family and ethnicity are the two pillars of the continent’s sociology.

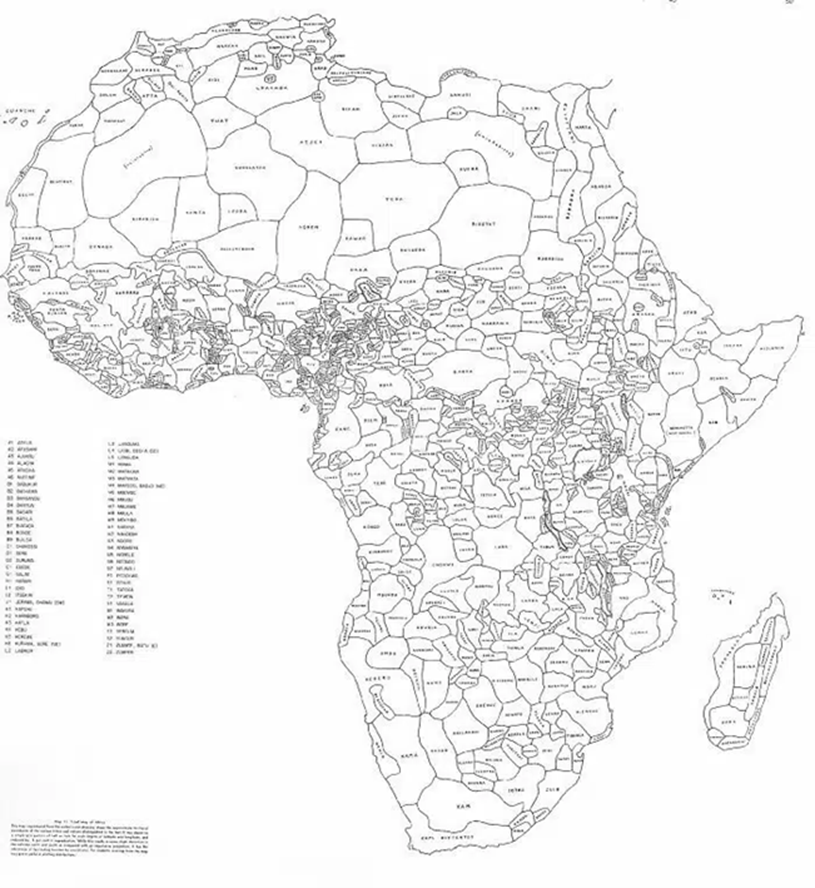

Africa is often presented as a mosaic of peoples and cultures (there are more than 1,000 ethnic groups on the continent), this is the main characteristic of its sociology because ethnicity is the foundation of solidarity and community cohesion much more than the nation-state.

The key aspect of the ethnic fact is the feeling of belonging. Ethnicity serves as the basis of identity to which individuals refer, grounded in a claimed common ancestry—whether real or mythological. Multi-secular or invented by the colonizer, claimed by individuals, whatever its scientific reality, it can be mobilized militarily, as was tragically the case in Rwanda, or to benefit from hospital care or, even more peacefully, to engage with a musical tradition.

Common ancestry is recounted in great founding myths that exist throughout the continent, some of which are common to several ethnic groups. These cosmogonic myths still serve as references in contemporary times; they are transmitted today through written literature after having been transmitted orally.

At the same time, the systems of kinship, extended family, clans, and lineages—built on the foundations of common ancestors, in this case, real—form the fundamental social bases that contribute to societal stability.

Pre-colonial social structures and the management methods that characterize them coexist today with modern states. Social relations are regulated according to distinct social levels and social regulations, including certain legal aspects, escape state authority.

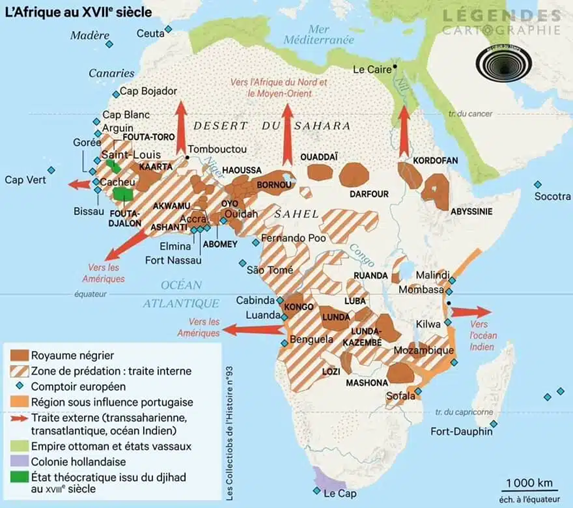

Indeed, the nation-state and related concepts were brutally imported through colonization without any time for historical maturation, particularly in segmentary and lineage-based societies. Many regions in Africa had no prior chiefdoms or centralized states, relying instead on lineage-based socio-political structures. Even where powerful kingdoms or empires existed, their political organization differed from the Western model, as territorial boundaries were not rigidly defined. This forced importation created challenges, including internal conflicts and identity struggles. Nevertheless, pre-existing institutions have persisted both in practice and in law, with many modern states continuing to entrust functions to traditional chiefs even today.

However, the two systems do not operate on the same basis, and the functions of the customary chief are culturally very far removed from those of a central or local administration official. The relationship between land and power is notably very different from the purely legal conception, and there is a sacred component that is obviously absent from administrative offices.

In some places in West Africa, in about fifteen countries (Mali, Guinea, etc.) and as many ethnic groups (Malinke, Bambara, etc.), there is also a system of castes linked to the profession inherited from the Mali Empire of the 13th century. The most typical castes are those of blacksmiths (considered, even in societies without castes, as having special relations with the spiritual world) and griots, bearers of traditional oral culture.

The African relationship to land and the forms of agricultural production organization are distinct from their counterparts on other continents. Concerning agricultural production, the common lot, including in Africa, is the stage of peasant society, organized around family self-production.

A key distinction from other parts of the world is the perception of land as something beyond mere material possessions. Rather than being formally owned by an individual—whether an ordinary citizen or the leader of a political entity such as a chiefdom or an empire—land is regarded as a shared resource, deeply connected to the collective identity and stewardship of the community. As one perspective notes. As a result, African land tenure, including in contemporary times, remains distinct from Western and Asian conceptions and is inherently complex.

This was not without causing difficulties at the time of colonization. Thus, the practice of British indirect rule, consisting of relying on indigenous leaders, led to the creation of chiefs where there were none. For example, this was the case in Nigeria for the Igbos; their decentralized social system, unsuited to European conceptions and colonial aims, which required a territorial chief, led to the creation of artificial chiefdoms.

From this conception of the relationship to land arises a land issue. At present, customary law and modern land law are still in competition, the former being directly attacked because it is considered to prevent the modernization and development of agriculture on a continent plagued by food insecurity. Women represent up to 70% of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa, but customary law means that they do not have title deeds to the land they farm, with custom only granting usage rights. Knowing that, moreover, only 10% of rural African land is registered, 90% is therefore managed informally and customarily. The development of land ownership and the recognition of women’s roles are therefore considered essential levers for the agricultural advancement of the continent.

For more information :

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

- https://africacenter.org/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024