Even though Ethiopia was never colonized and despite some early independence (Liberia in 1847 and the Union of South Africa in 1910), the beginnings of African emancipation date back to the First World War.

For Europeans, this conflict was an opportunity to rub shoulders with African “brothers in arms” (more than a million Africans were mobilized), which changed their view of them. For Africans, the war made it possible to break with the unbalanced relationship between the colonized and his “master.” The Treaty of Versailles of 1919 stripped Germany of its colonies, which the victors shared among themselves, which roughly traced the borders of present-day Africa. Anti-colonial sentiment continued to develop in Africa after the war, as well as, modestly, in Western countries. American President Woodrow Wilson, in his peace program (Wilson’s Fourteen Points), written in advance of the Paris Peace Conference (1919), explicitly mentions the self-determination of peoples, which inspired and legitimized anti-colonialist and African nationalist movements. These movements made themselves heard, such as the Wafd, an Egyptian delegation that wanted to participate in the Paris Conference to plead for the independence of Egypt and whose members were deported by the English authorities. Some obtained a hearing by the League of Nations, such as the National Congress of British West Africa, an independence movement from the Gold Coast (now Ghana), represented by J. E. Casely Hayford, which obtained an international hearing in the early 1920s. As a result, the 1930s saw the rise of forms of resistance and unionization that would later lead to independence. However, at the same time, in 1931, in France, the colonial exhibition was organized, symbolizing the unity of the “greater France”, following the British Empire Exhibition of 1924. At that time, like France, the metropolises were not ready to detach themselves from their colonies. The empires had made it possible to win the war, thanks to the men, mobilized by force, and the resources, requisitioned to supply the mother countries. In 1935, fascist Italy even decided to invade Ethiopia, where it remained until 1941, demonstrating persistence in the colonialist ideology.

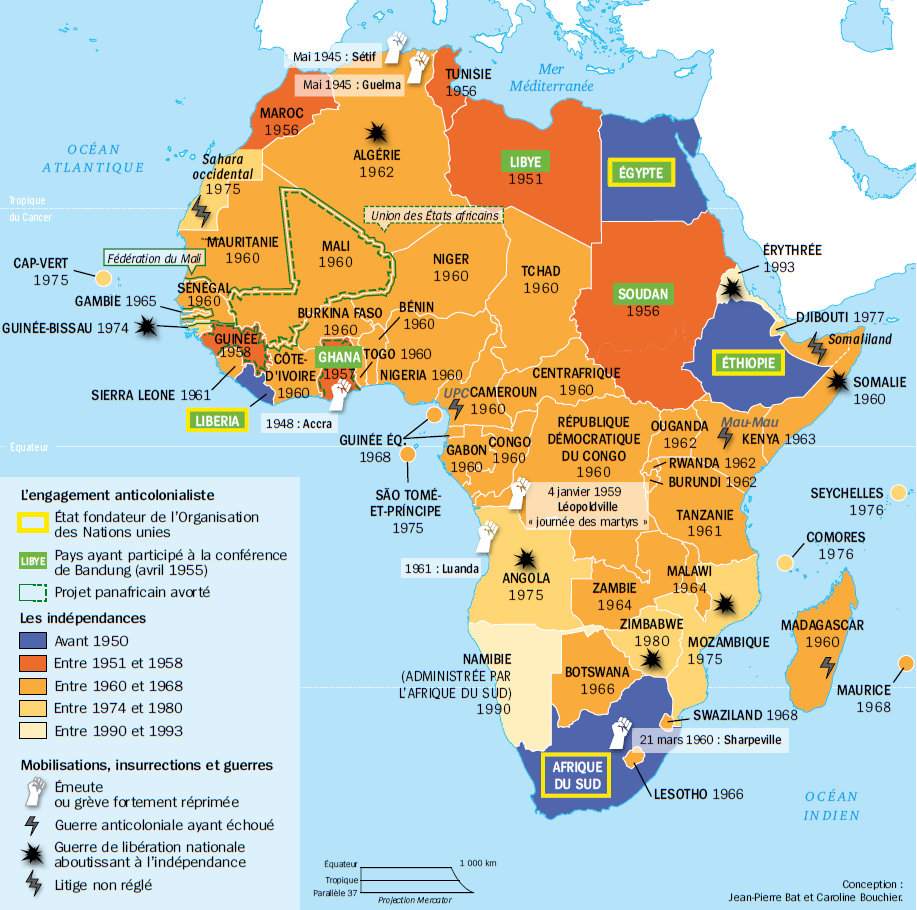

The Second World War was a crucial turning point. During the conflict, the “colonials” distinguished themselves once again on the battlefields, mobilized in their hundreds of thousands, mainly by France and England. In August 1941, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Atlantic Charter, which foreshadowed the United Nations Charter (1945). The evolution of ways of thinking following the war tended to make the very idea of colonialism unbearable. The year 1945, the end of the war, was also the date of the Pan-African Congress in Manchester, which marked the beginning of militant Pan-Africanism. The post-war period saw African elites, trained in the United States or in Europe (Julius Nyerere, Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Nnamdi Azikiwe, etc.), take charge of challenging the colonial model, denounced as being in the exclusive service of the Whites.

Political parties were created, such as the Convention People’s Party (Gold Coast or Côte-de-l’Or, present-day Ghana, 1949), the African Democratic Rally (federation of political parties of the French colonies, 1947) … whose leaders would be the main politicians of the future independent states.

For more information :

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

- https://africacenter.org/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024