In 1914, due to the rise of colonial empires, the “dark continent” had only two sovereign states, Abyssinia (or Ethiopia) and Liberia. Since the Second World War, the number of independent African states has continued to increase, from 4 in 1945 to 27 in 1960, reaching 53 in 1993 and 54 in 2011.

The borders of African states are largely the result of colonization. As for the grouping of different countries into sub-regions, it is used more for practical reasons than a historical reality.

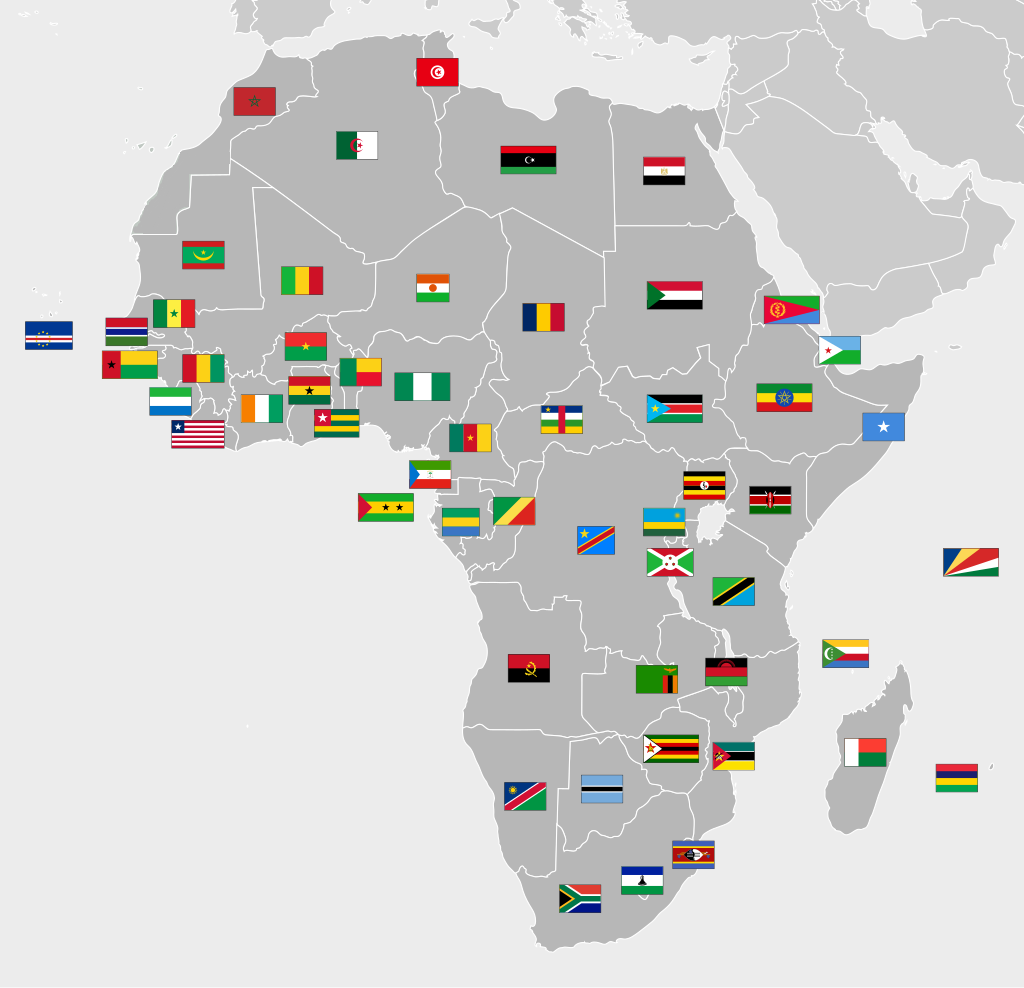

Regions of Africa according to the UN85:

We generally distinguish:

- North Africa, bordered to the south by the Sahara, inhabited by predominantly Arab and Berber populations;

- Sub-Saharan Africa, itself subdivided into four sub-regions:

- West Africa,

- East Africa,

- Central Africa;

- Southern Africa consists of all the territories located south of the equatorial forest.

African states are part of borders that largely stem from colonization, endorsed and protected by the OAU in 1963.

They are often described as artificial and, as such, considered causes of conflict, incoherent due to their delimitation of politically weak spaces, and illegitimate because they do not reflect prior ethnic or historical realities. Moreover, the notion of a demarcated border is culturally foreign to sub-Saharan Africa, especially in societies with ‘diffuse power,’ where social organization is decentralized, and governance is shared. In these contexts, land is not viewed as a commodity to be owned, and the Western-style nation-state remains an imported concept.

However, some argue that these borders are not entirely artificial, with examples like the Niger-Nigeria border, which roughly follows the contours of an earlier caliphate.

The economic curse of borders is often overstated. Ethnic ties and shared vehicular languages frequently extend beyond officially recognized (de jure) boundaries, leading to significant internal movement, especially in cross-border trade among members of the same ethnic group. This trade benefits formal states through customs revenues, which can account for as much as 30% to 70% of some national budgets. However, the lack of infrastructure leads to long waiting times at the border, contributing to high transaction costs. Ultimately, African borders are porous and easy to cross, whether legally or illegally, presenting opportunities for economic operators.

As for ethnic conflicts, they are largely independent of borders, remaining sometimes internal to a country, and sometimes cross-border depending on local configurations.

Between 1963 and 2022, the International Court of Justice ruled on eight border disputes in Africa, such as the Aozou Strip in Chad in 1994 and the Bakassi Peninsula in Cameroon in 2002, while other cases are piling up, such as the question of the sovereignty of the island of Mbanié filed in 2021.

In the 2010s and 2020s, border conflicts arose over the control of natural resources, such as between Kenya and Somalia over fish resources or between Equatorial Guinea and Gabon over hydrocarbons, as well as secessionist conflicts such as the one over South Sudan. In 2022, large territories still have no defined status, such as the Ilemi Triangle and the Halayeb Triangle. Former colonial powers are sometimes still at odds with their former colonies. This is the case for Spain and Morocco over the cities of Melilla and Ceuta, France and Madagascar over the Scattered Islands, and the United Kingdom and Mauritius over the Chagos Archipelago.

In 2021, in North and West Africa, 60% of victims of violent events were less than 100 km from a border, particularly due to the presence of transnational armed groups, such as jihadists. The further away from these areas, the lower the number of deaths.

For more information :

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portail:Afrique

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Africa

- https://africacenter.org/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/

- https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/

- https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents-publications/economic-perspectives-en-afrique-2024